Nyquist is Not Broken: Part II

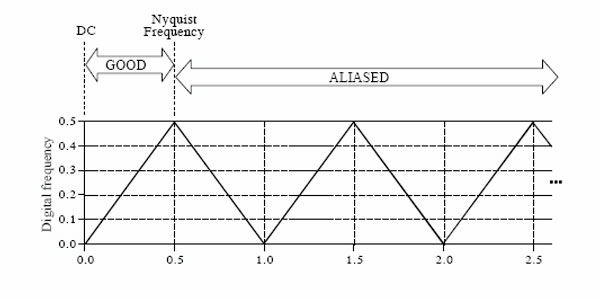

Today’s installment pushes forward on the basic theory of The Sampling Theorem, which is the basis for converting analog music signals to PCM digital versions. We talked about the idea of “proper sampling”. The concept is that a set of data points associated with the amplitude of a continuous signal can describe one and only one waveform. I acknowledge that it requires us to stay within certain ideal conditions like staying within the Nyquist Frequency or half of the sample rate. The elementary steps that we’re taking are deliberately meant to keep things simple and in plain English.

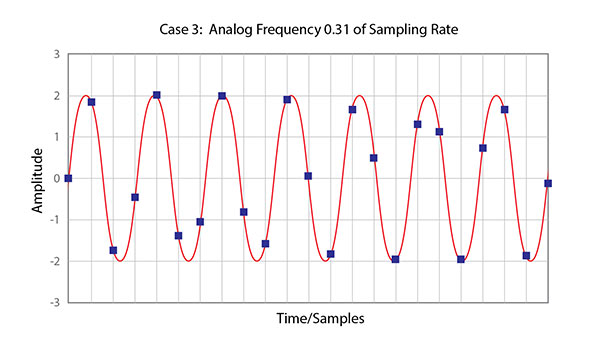

Yesterday I presented the trivial case of a straight line and a signal with a frequency that was only 9% of the sample rate. The 9% waveform looks very much like a sine wave and intuitively we know that it could be represented by the sample data points. Let’s raise that number to 31% and see if there is a clearly identifiable waveform presented by the set of samples. Take a look at Figure 1:

Figure 1 – An illustration of a signal that is 31% of the sampling rate and the associated set of sample points. Notice that they don’t show a clear representation of the singe wave.

The Sampling Theorem states the a continuous waveform that is digitized and only 31% of the sampling rate can be reconstructed from those data points even if there is not obvious sine-like graphic. Theoretically, there is still only a single analog since wave that will match with the samples. We’re still good here…given that no other frequencies are present. Remember that sine wave do not have any partials.

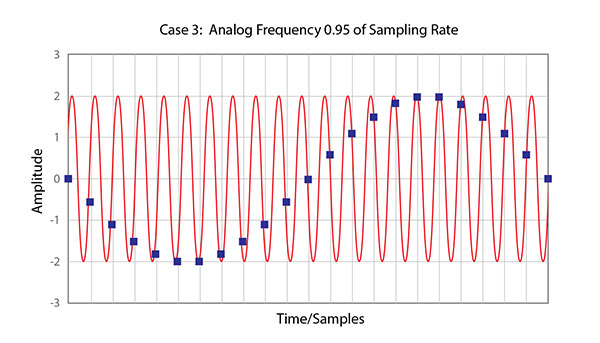

Finally, take a look at what happens when a continuous waveform that is 95% of the sampling rate is digitized:

Figure 2 – An illustration of a signal that is 95% of the sampling rate and the associated set of sample points. While there is a clear sine wave shown in the data points, it is NOT the original source signal.

What happened is called aliasing. I’ve talked about this digital artifact previously (click here to read the original article). The Sampling Theorem states that any signal component presented to a digitizing system that exceeds the half of the sampling rate (Fs/2) will “break” the system. We can clearly see this in the graphic above. We don’t have the uniqueness that we had before. Now there are several sine waves that can be rebuilt from the same set of samples.

This is where the theory stops and the practical engineering starts. There are knowledgeable engineers that would have use believe that Nyquist is broken if a system allows for any frequencies higher than Fs/2 and results in aliasing…at any amplitude! Another criticism says that Nyquist is all well and good for sine waves but that it falls apart when complex waves forms are introduced.

We’ll take a look at these and other issues in a future post.

+++++++++++++++++++

I’m still looking to raise the $3700 needed to fund a booth at the 2015 International CES. I’ve received some very generous contributions but still need to raise additional funds (I’ve received about $2200 so far). Please consider contributing any amount. I write these posts everyday in the hopes that readers will benefit from my network, knowledge and experience. I hope you consider them worth a few dollars. You can get additional information at my post of December 2, 2014. Thanks.