The Birth of DSD Part III

By the time Sony and Philips completed the design and manufacturing of their first SA-CD machines (which were limited to stereo playback initially), the chip makers had already made advances in the design of their chips. It turned out that analog to digital converters had abandoned clocks of 64fs (64 times 44.1 kHz) and moved to 128fs. And they determined that using only a single bit wasn’t the best technology either. The state-of-the-art moved beyond 1-bit (from 1.5 to 5 bits). The imagined simplicity of the original Sony plan failed…to stay current with the new chips they needed additional processing, which was not part of the new player designs. Sony and Philips were forced to live with the older design based on the capacity of the discs (which held the same amount of data as a standard DVD…4.7 GB). The original SA-CD players and discs used DSD 64 and analog filters…and they were produced from analog and PCM masters.

In spite of the generosity of Sony, no one with a commercial recording facility opted into their free equipment program. Sony went to production facilities and mastering houses offering free or heavily discounted Sonoma DSD systems. After all, if a new consumer audio format is going to get the traction that it needs to succeed in the marketplace, there has to be a whole bunch of new SA-CDs being released. If there aren’t any studios using the DSD system then the pipeline will remain dry.

I heard about the DSD hype at the time. I spoke to some folks at Sony about the Sonoma system and the theory behind the whole 64fs 1-bit miracle that was going to bring new levels of “analog like” fidelity to the digital world. I read the white papers, talked to experts, listened to the releases, and ultimately decided that it wasn’t for me and wasn’t ready for commercial release either. I stuck with high-resolution PCM and the DVD-Audio format.

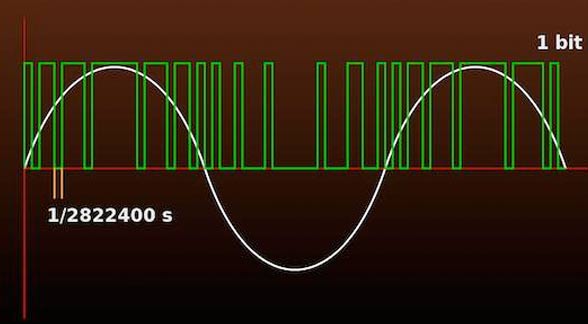

The biggest obstacle ins adopting DSD was the lack of a DSD production chain…and obstacle that remains to this day. You simply can’t produce a native DSD recording without adopting very stringent limitations…limitations that commercial studios will never accept. The original Sony plan of digitizing their catalog of analog masters is the perfect place for DSD. The reason is that you’re doing a straight transfer of an analog master tape to a digital bitstream at 2.8224 MHz and 1-bit without any modifications. The white papers written at the time (and some contemporary papers) still talk about the 1-100 kHz frequency range of DSD. The reality is DSD 64 is only acceptable to just past 20 kHz…because if you extend the range to 100 kHz you can only record 6 dB of dynamic range. Remember that DSD is only 1-bit long and a single bit translates to 6 dB!

Those working in DSD have adopted a multiple conversion approach whenever they want to produce a “native” DSD project if they want to work in the digital domain. They record in high-resolution PCM and then do all of the post production work in PCM prior to conversion to DSD. How high is the “high-resolution PCM”? Well, it’s 8fs or 352.8 kHz and 24-bits, which is also known as DXD (Philips wanted to distance themselves from the term PCM…rest assured DXD is high-resolution PCM).

It is also possible to produce DSD releases by recording and posting everything in the analog domain. There are a few companies, engineers, and producers that record to analog tape, mix through their analog tape machines, use lots of analog and PCM digital processors, and then output to DSD. Just how “native” or “direct” is this production chain? And does anyone really think that this production approach delivers fidelity that is better than the analog tape machines that we used 20-40 years ago?

I was surprised to read about a new “Basement Tapes” project being produced by T. Bone Burnett. He and his engineer are big fans of analog recording. They like the sound and the “warmth” etc. So they recorded the project on a Studer A827 24-track analog machine. I’m sure it’s exactly the sound that they want but it will always be bound by the technology used to make the initial recording.

There is no escaping the hard fact that commercial audio production is going to done using PCM. It’s an open question whether the producers and engineers making these new recordings will care about high-resolution. I doubt they will. And it doesn’t help much when the mixing or mastering engineers simply make the last transfer at high-resolution rates…in PCM or DSD.

Tomorrow, I finish this little rant by talking about “best practices”.