Hi-Audio — Getting the Basics Wrong? Part II

It’s another rainy day in Southern California — time to follow up on the blog I started the other day. The first part is available at Hi-Res Audio — Getting the Basics Wrong? I was critical of an article that purported to lay out the basics of Hi-Res Audio. The piece was full of inaccuracies. In fact, it’s actually difficult to find any on line sources that present the truth about Hi-Res Audio.

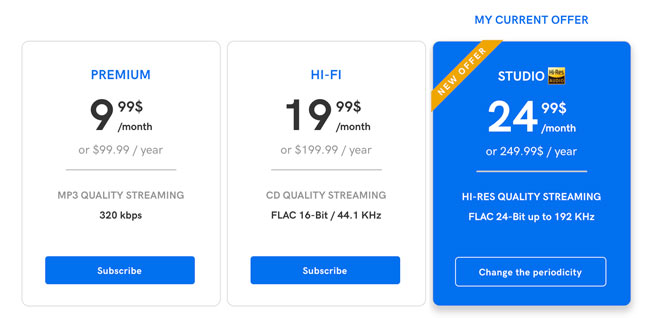

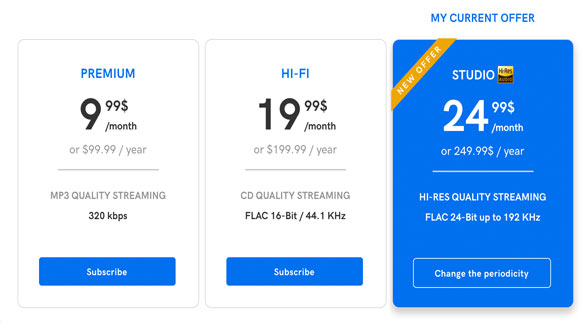

Interestingly, yesterday Qobuz launched its “Hi-Res Audio” streaming service yesterday in the United States. I signed up for the FREE month of hi-res audio streaming. I’m streaming THE BEATLES “White Album” at 96 kHz/24-bits as I write this (which was definitely recorded during a time when high-resolution audio wasn’t even dreamed of). Qobuz offers three tiers of service as outlined below:

After clicking around on their website for additional information about the “quality” of the audio available at each level, I found a section titled, Discovering and Understanding High Quality Sound.

The opening paragraph introduces their approach to fidelity:

“Many people still ignore how much compression robs music of the emotion and depth it should bring. Respecting sound means understanding the words that describe it. It also means fighting against the sometimes deceptive misuse of its lexical field: High Fidelity, HD, HIFI, Lossless, CD Quality, Hi-Res – We will help you find your way”.

I love that Qobuz is fighting against the “deceptive misuse” of audio terminology and are willing to help us find our way. Maybe they should start by removing the “Hi-Res Audio” logo discussed in my last blog…it is reserved for hardware and has no business on a site that delivers music downloads or streams.

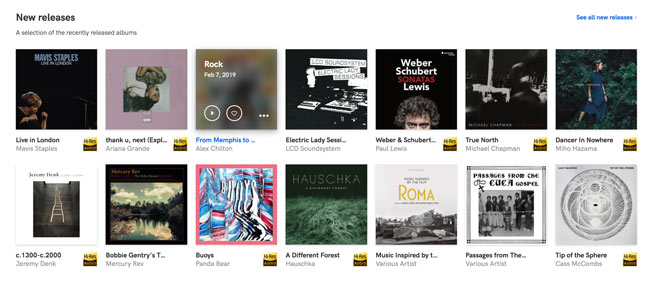

The graphic that Qobuz uses to describe the “quality” levels includes written descriptions as well. I posted a copy of the “stair step” illustrations in my previous post but have included it below. The notion that PCM digital encoding creates a series or stair steps is patently incorrect. I have to admit that years ago, I drew pictures similar to those below. Subsequent study and research made me realize that samples are points of data NOT stair steps — AND those points can be used to perfectly reconstruct the original waveform.

So here’s the description of MP3:

Named for its format, the MP3 is a compressed lossy audio file: it contains less data than the original files. The compression process entails the loss of many aural details, especially the harmonics of higher-pitched sounds. This results in pronounced quality loss, but also in small storage space. With improved internet connections, part of it’s interest has been lost.

Lossy compressed format • Bitrate: from 128 kbps to 320 kbps • Resolution: 16-Bit

The MP3 format is a lossy audio compression process that reduces the data and bandwidth needed to represent an audio selection. “Lossy” means that some of the information in the original digital representation — the uncompressed version — is not present in the MP3 compressed version. However, it is arguable whether “many aural details” are lost in the process. If the bandwidth is maintained at 320 kbps, an MP3 file can be difficult to spot compared to a CD — very difficult! Qobuz doesn’t say that their lowest tier is always at 320 kbps. It’s possible that they deliver 128 kbps, which while still pretty good, does start to fall into non-audiophile quality levels.

CD Quality:

CD Quality comprises a number of formats (FLAC, ALAC, WMA Lossless…) offering lossless compression at a certain resolution and a certain sampling rate (16-Bit / 44.1 kHz -) which are identical to those used by the CD, defined according to the Nyquist-Shannon theorem. This nondestructive compression method reduces the file size without changing the original quality. Its bitrate is over 4 times higher than MP3’s.

Lossless compressed formats • Bitrate: up to 1411 kbps • Resolution: 16-Bit

As mentioned in the previous article, it is important to notice that Qobuz and others use the term “CD Quality” instead of CD Spec or Redbook Spec. They hope that consumers will equate them. In fact, they are not the same. Either something meets the CD Spec or it doesn’t. “CD Quality” might be indistinguishable from the real deal but vendors should be more clear. Strictly speaking, “CD Quality” can be produced by a really good quality MP3 file at 320 kbps. “CD Quality does not require the use of lossless audio compression techniques like FLAC, ALAC, MLP, or WMA Lossless.

I’m not sure why they mentioned the Nyquist-Shannon Theorem in defining “CD Quality”. It doesn’t have any bearing on lossless compression or “CD Quality”.

The final line — the one in bold type above — is important for those subscribing at the “CD Quality” tier. They state that they are going to deliver “up to 1411 kbps” using a lossless codec. They means that they could provide lower than CD Spec — as long as it is indistinguishable from the fidelity that we associate with CDs. The bandwidth of a Redbook CD is never lower —or higher — than 1411 kbps (44.1 Khz * 16 bits * 2 channels).

And finally Hi-Res Audio:

Hi-Res (as in High-Resolution) represents the apex of digital audio. These files – obtained through lossless compression or uncompressed – deliver better sound quality than a CD. They are encoded in 24-Bit, at frequencies that can go up to 192 kHz – these are actually the same files that are used in recording studios.

They therefore offer a much more accurate, faithful and respectful reproduction of the work of artists and sound engineers than any other audio file format. Moreover, the listening intensity and richness has no comparison with MP3 files or even with CD quality!

Uncompressed or lossless compressed formats • Resolution: 24-Bit

So we’ve arrived at the “apex” — the highest point of digital audio according to Qobuz and we’re going to be charged $24.99 per month to receive “hi-res audio” via streaming. We can expect to get the “same files” — the same masters — that are used in the recording studios. Well, as the owner of a studio and producer of hundreds of real hi-res audio productions, we ONLY use uncompressed audio during the production phases of a new project — not losslessly compressed files.

Qobuz subscribers at this tier should thrill that they’re getting up to 192 kHz/24-bit audio through their DACs. But do the files deliver the full potential of 24-bits? Does anyone think that the dynamic range of any popular commercial audio album released in the last 50 years require 24-bits or that their hardware is capable of reproducing dynamics beyond a CD at 16-bits, or that their listening environment is quiet enough to make that sort of dynamic range perceptible? Of course not.

As a former mastering engineer, I worked on hundreds of commercial albums. I can state with great confidence that I never delivered an album that used even 16-bits of dynamic range. Most albums — as you know if you look at the loudness database — rarely use more than 8-10 bits of dynamic range. Analog tape tops out at about 10-12, so why bother bragging about 24–bits? It only matters if the original master uses all 24-bits!

And forget about anything higher than 96 kHz — it’s all you’ll ever need to get fidelity beyond your system’s ability to play it back and your ears to hear it. Using 192 kHz is simply a sales gimmick for people impressed by large numbers.

But it’s the subjective narrative that should steer you away from the premium tier of the Qobuz streaming service. The “hi-res audio” streams (or files) available on Qobuz do not offer “a much more accurate, faithful and respectful reproduction of the work of artists and sound engineers”. This is pure sales hype. The writers of this copy would like us to believe that $25 per month will bring a perceptible improvement in sound quality. It won’t. It is wishful thinking to state that their hi-res audio digital music — virtually all of which derived from standard-resolution masters — will eclipse the fidelity of CDs. I would challenge the sales people at Qobuz to take my HD Audio Challenge. I suspect they will discover that human perception cannot detect fidelity differences between a hi-res audio files and a CD downconversion. I would even bet money that a well done 320 kbps MP3 wouldn’t be noticed among full res Redbook files.

Glossary

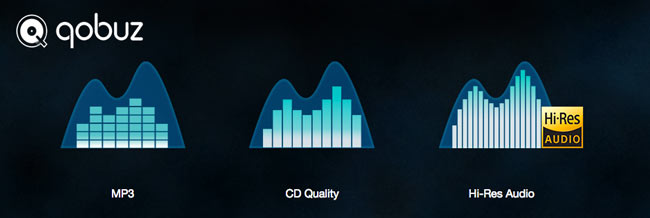

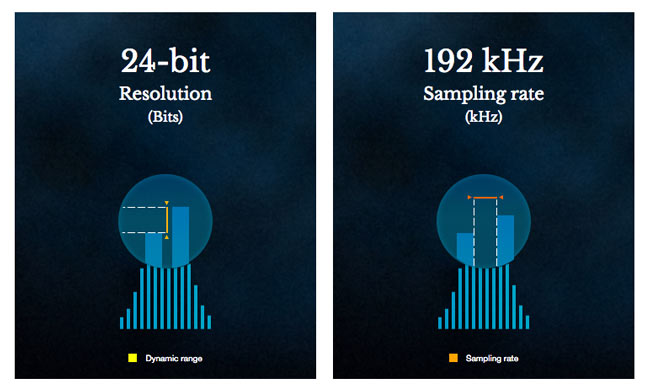

Later on the same page, Qobuz’s writers attempt to define Resolution and Sampling Rate and accompany their definitions with nice illustrations. See below:

24-Bit Resolution (Bits)

Resolution is expressed in Bits. It determines the accuracy of a sound’s dynamics – in other words, the number of values a sound can take. The higher the accuracy of a sound’s dynamics, the more perceptible aural variations will be, and the deeper a sound will seem. Sound becomes deeper and more dynamic. In 8-Bit, a sound can have 256 different values. In 16-Bit, it can have 65,536 values – and in 24-Bit… 16 777,217!

One element of resolution is word length — the number of bits in each digital sample. There are other factors that determine the “resolution” or accuracy of an audio recording and reproduction including sample rate, clock, and more. Thinking of resolution as merely the number of bits is like thinking the number of bits behind each pixel on a computer monitor or television display defines video resolution. The number of bits does establish the potential dynamic range of a specific digital system. Each bit is roughly equivalent to 6 dB of dynamic range (recall that DSD encoding at 1-bit provides only 6 dB of dynamic range unless noise shifting pushes all of the in band noise beyond the range of human hearing).

But merely adding bits doesn’t translate to “more perceptible aural variations” or make a sound “deeper”. Wider dynamic ranges can be captured — or the noise floor lowered — when longer words are used to digitize a source but if the sources don’t require excessive dynamics then the extra bits are useless. I advocate for recording engineers to use 24-bits when capturing a performance but consumers do not need — nor can their systems benefit from — 24-bits.

What does it mean to say, “In 8-bit, a sound can have 256 different values?” If the source recording has less than 48 dB of dynamic range, then all of the dynamics present can be faithfully encoded in 8 bits. The exponential increase in the available amplitude levels made possible by increasing word lengths from 8 to 16 to 24 (and 32) ultimately comes back to 6 dB per bit in dynamics. A CD can deliver over 90 dB of dynamic range. I challenge anyone to find me a commercial albums that uses anywhere close to that amount (my own AIX Records recordings are excluded).

192 kHz Sampling Rate (kHz):

Sampling an audio signal consists of measuring a signal’s amplitude at regular intervals, which are predetermined by the sampling rate. The latter is expressed in kHz (kilo-Hertz). The higher the frequency/rate, the most faithful and accurate the transcript will be. CD quality (44.1 kHz) collects 44,100 samples per second. In Hi-Res, this rate can reach 192 kHz (6.5 times more than a CD!).

Again, the writer gets the essential facts right but then leaps to a ridiculous comparison. Yes, 44.1 kHz — the sample rate of a Redbook CD — is 6.5 times less than 192 kHz. But it is NOT true that a 192 kHz digital file sound 6.5 times better than a CD — they don’t. This reminds of the crazy comparisons made by DSD advocates. SACDs, which use DSD, are 64 times better than CDs because the sample rate of 2.8224 kHz is 64 times 44.1 kHz. No one mentions that they use only a single bit and that DSD uses a fundamentally different encoding scheme.

Sample rates in a PCM encoded audio recording determine several critical elements in a digital audio files. The first is the highest frequency that can be properly recorded (this is where mentioning the Nyquist-Shannon Theorem would be appropriate). Increasing the sample rate increases the highest frequency that a digital system can capture. These ultra high frequencies are typically partials or harmonics of the actual notes and determine the brightness or timbral complexity of a tone. It should also be noted that going from 10,000 Hz to 20,000 may seem like a very large margin but in fact, it’s only another octave. When an Mp3 lossy encode strips off the last few thousand Hertz, the timbral change is pretty minimal.

Higher sample rates also make LPF (Low Pass Filter) designs in ADCs and DACs simpler and more elegant as well as contributing to lower noise floors and spatial integrity. But as I’ve stated on many previous occasions, a maximum of 96 kHz is all that is required for full fidelity.

Honest Alternatives – Truth in Advertising Hi-Res Music:

Qobuz claims to have access to 170,000 hi-res audio tracks. The fact that they’re aren’t even 2000 albums that have been produced at real hi-res doesn’t seem to matter. What they and other companies should be pitching should rightfully be called “hi-res transfers”, standard-resolution masters digitized at high-resolution specifications! Some years ago I pushed really hard at the CEA high-end audio board for honestly in the emerging world of high-resolution recording and playback. I was ignored (and was finally kicked out of the group). On a flight back from one of the New York City meetings, I designed a logo for what HDtracks, SuperHiRez, Qobuz and others were selling falsely as “hi-res audio”. See below:

There is only one reason why companies — any company — choose to push standard-resolution music as something that it is not — money. The entire industry from Sony and Universal Music Group to Warner Brothers and Neil Young to Qobuz and MQA to Stereophile and TAS uses the myth of hi-res audio instead of accepting the realities of the music industry and actual fidelity because they believe that they can sell more stuff. And they’re probably right to continue the falsehoods.

The truth is we already have the potential for amazing music recording and reproduction. We’ve actually had it for decades — and no I’m not talking about analog tape or vinyl LPs. The venerable CD — when properly made — can reproduce amazing, mind blowing fidelity. The industry should focus its marketing efforts on convenience (streaming a wonderful thing), affordable subscription rates for all levels of fidelity, consistency in messaging, and truth in advertising. Meanwhile, the producers and engineers should start pushing NARAS and the labels to allow them to make better sounding records.

I suspect none of the craziness will change anytime soon. I’ve been listening to Qobuz and the Neil Young Archives at 320 kbps and 96 kHz/24-bits — and capturing the output of my Benchmark DAC 2 — for analysis. I”ll share my findings soon. The short answer is save your money.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

My younger brother is in need of some help. This isn’t the place or platform to relate the details of his current situation but I know some of you might consider making a contribution to the GoFundMe campaign I started for him once you read the narrative I authored. In fact, since I posted this a week ago, many readers have given generously…thank you!

I wouldn’t make this appeal if I didn’t feel his circumstance was compelling and the person worthy. If you want to read more, please click the link below and consider making a contribution.

To thank anyone that makes a donation of $100 or more, I will send a signed copy of my “Music and Audio: A User Guide to Better Sound” (with Blu-ray Demo disc) AND a FREE copy of the latest AIX Records sampler— a $25 value. If you contribute $50 – $100, I’ll send the eBook, downloadable files, and the AIX sampler. Finally, for a donation of $25 – $50, you’ll receive the eBook and demo files.

I will cover all shipping expenses for domestic orders. International shipping will be additional.

Click here to be taken to the GoFundMe page.

Please do not share this link. Thanks for your consideration.

Now let’s imagine if instead of creating an impossible higher quality for the “hi-res” offer, one simply and purposely introduces a poorer quality to the mp3 and CD offers, by adding noise, cutting high frequencies etc…

The result would be a measurable difference in quality between the three offers. Sold. Or? 🙂

Malicious thinking I know…

Interesting article. Thank you.

Kind regards,

Interesting idea…one that I experienced with the AudioQuest cable controversy some years ago. I have captured some of the streams and will be reporting soon.

Yes, getting the basics wrong. To have any chance of “success” you need to follow a certain path.

What exactly are you trying to do?

What is the science behind the factors that govern that goal?

If the goal is one that is subjective, how do you know when you achieved your goal?

Are there factors you’ve placed great importance on that are irrelevant. The flip side is are there important factors you omitted?

What methodologies to achieve your goal have you considered? What are the pros and cons of each one? Which one gives the best chance of success and why? If it fails what other methodologies would you consider?

What is the purpose of achieving your goal? Making a profit on it? Gaining scientific knowledge? Just exploring something unachieved yet for personal satisfaction? All three are legitimate reasons. If your goal is to make a profit, is your product of a nature meaning cost, complexity, uniqueness, reliability to a sufficient degree to be adequately attractive to a large enough and affluent enough market?

Are there any other basic questions I’ve omitted? Have you thought about and gotten satisfactory answers to all of them? If the answer is no, what will you do about it if anything? What do you expect your chances of success will be? How well is your effort so far doing and what are its prospects? Is it on track to be “the next big thing” or is it just a small niche that will remain a flash in the pan?

You say:

“The fact that they’re aren’t even 2000 albums that have been produced at real hi-res doesn’t seem to matter.”

Is there a way that number can be verified ?

I’ve tried google number of albums available as general in HDtracks, MQA, etc, and impossible to find.

I think there exist 1500+ DSD, but that’s not what we’re talking about here I hope.

And just to keep it simple, let’s define real hi res as 24/96 or better at the moment.

I arrived at that number after looking at the number of new recordings that were actually recorded and released at 96/24 (or DSD 64) or better. Virtually none of the albums on HDtracks and the other hi-res music sites qualify. They are hi-res transfers of older standard-res masters. Real Hi-Res music albums are only produced and delivered by audiophile labels. Just because some uses 96/24 bits during the recording stage doesn’t mean that the potential of those specs survives to the distribution format.