Recording Piano: A Struggle for Accuracy

Capturing the sound of a 9-foot Steinway Model D grand piano is a daunting task. While the king of all instruments may be the mighty pipe organ, the piano comes in a close second. The complex nature of the timbre of a piano, the wide range of dynamic levels and the “pearl-like” tone of a great instrument challenges even the most seasoned audio engineer. And just as there are a variety of instrument makers, there are lot of different approaches to recording a piano.

I remember one particular conversation with Elliot Mazer, a very well-known audio engineer that has worked extensively with Neil Young over the years. His approach to capturing a grand piano is to place a single condensor microphone (a very high quality microphone with lots of high end extension) a couple of feet in front of the instrument. He argued that his arrangement would result in a smooth blend of the entire piano register and more importantly be phase coherent when it came time to master the recording. This may work great in the days of mono LPs but the lack of dimensionality or depth in the piano sound along with the single point source is not to my taste. I want a the piano to sound full and expansive.

A more traditional approach for classical or jazz recordings is to place a stereo pair of microphones about 10-15 feet back from the instrument. This technique enables the engineer to capture the sound of the room, the reverberation present in the space. In a live performance auditorium, this approach works quite well. Many engineers endorse a method named after its inventor Alan Blumlein. His ground-breaking (he invented it in the 1930s) technique was really the first to capture true stereo. The Blumlein “true stereo” setup includes to coincident pairs of bidirectional microphones. Records made with a “Blumlein” pair give great separation and are completely mono compatible, an important feature back in the days of LPs and mono radio broadcasts.

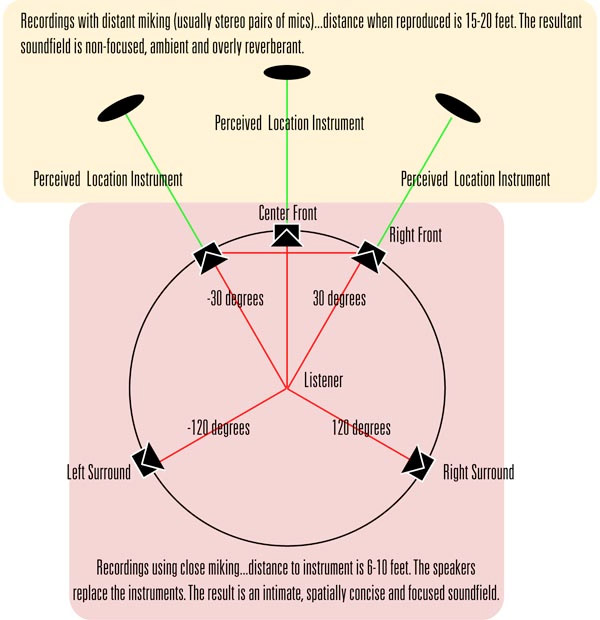

A diagram that illustrates the perceived distance to a recorded source.

My own approach has evolved over many years. I used to record a lot of classical music recitals and concerts. I would use a stereo pair of microphones (usually an ORTF pair…for those interested) hanging through the ceiling or at the edge of the stage on a long mike stand. When I started recording for my own label, I changed my thinking. I didn’t have a live audience around so I could place the microphones anywhere I wanted. The first project was a recording of the four Chopin Piano Ballades, which are absolutely beautiful pieces from the early Romantic period. I placed 16 microphones (8 stereo pairs) in a variety of locations around the instrument, at the edge of the stage and in the back of the hall. I had stereo pairs of microphones inside the instrument very close to the strings, mikes underneath the instrument, behind the performer, at the edge of the instrument and so on. When I returned to the studio to listen, I was able to carefully select from the various pairs until I found a sound the I liked. In the final analysis, I chose two close stereo pairs (one in XY and the other as an ORTF arrangement…see the picture) along with the mikes at the back of the hall. The sound is intimate and direct. Some prefer lots of reverberation and enjoy the sound of a more distant setup. But after several reviews of my Chopin vs. CDs released by Deutsche Gramophone and MCA Classics of the same works preferred the sound of my tracks, I stuck with this model.

One of my recent Blu-ray discs features a very talented pianist by the name of Bryan Pezzone. He is a great performer that is equally comfortable in the world of jazz as he is playing Mozart or Rzweski. When he came to the studio to hear the project that we did together he said, “Mark, I’ve been recorded hundreds of times and during playback I get about 70-80% of what I put into the tracks back through the speakers. When I hear your tracks, I get everything back…it’s all there…100%. Bravo!”

If it was as simple as placing just one microphone, we’d all be recording engineers!