Compression vs. Compression? Part II

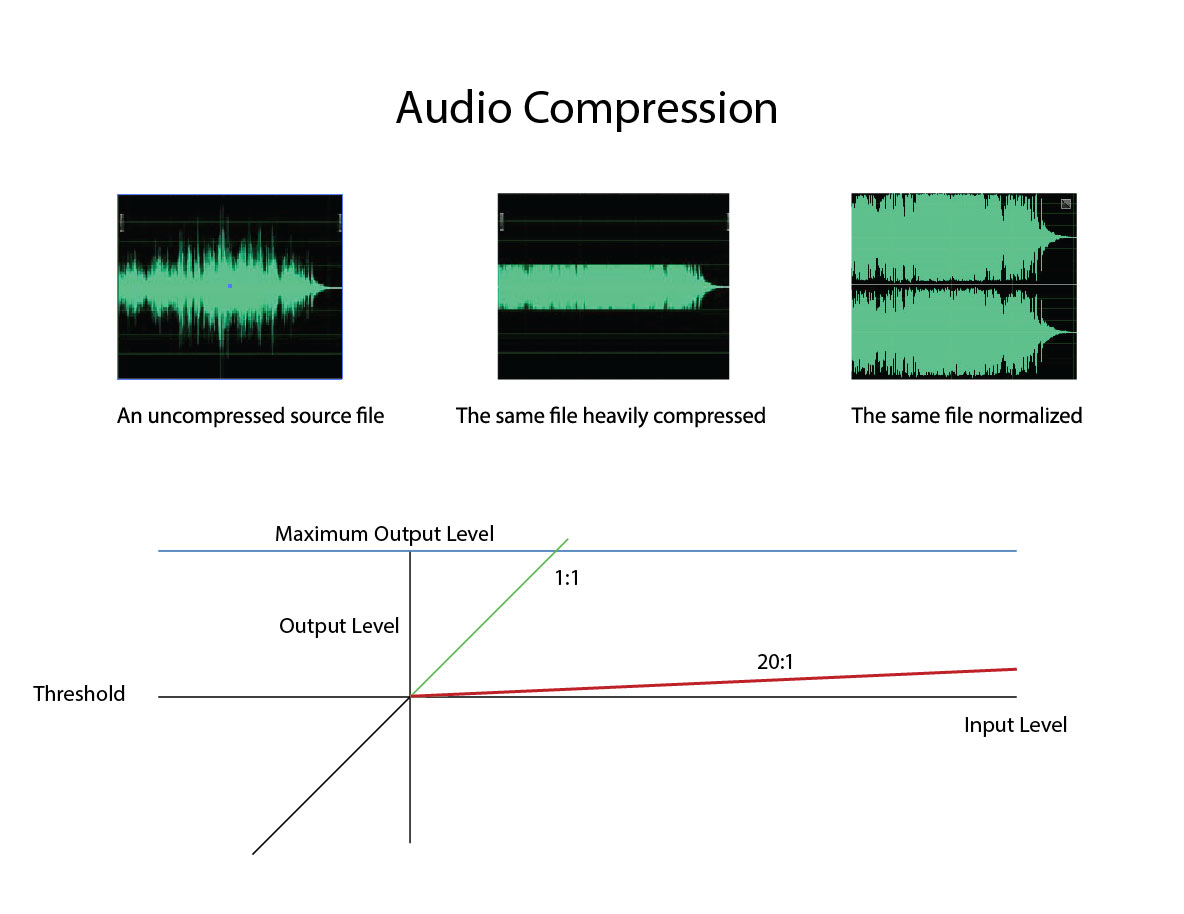

Take a look at the diagram that I’ve prepared below. It shows a number of things. The first three waveform displays show each stage of compressing a signal. On the left is the uncompressed signal. The wide vertical differences show the short and long term dynamics of the particular piece of music (this is the end of Mosaic again, which is available for download at the FTP site). The middle waveform shows what happens when a 20:1 compressor/limiter (a limiter is simply an extreme case of compression) is applied. Any part of the sound that exceeds the “threshold” level is reduced by a specified ratio…in this case 20 to 1, which is a lot. If a signal comes in below the threshold it is allowed to pass through undisturbed.

Figure 1 – Three images of a file subjected to compression and a transfer function showing the input and output from a compressor/limiter. [Click to enlarge]

The overall RMS level of the song is reduced and the resulting waveform shows the telltale plateau appearance of most pop music. This is how things are portrayed in “The Distortion of Sound” film. But the processing doesn’t stop there.

Not only are the engineers trying to protect their recordings from overages but they are also tasked with making the final output as loud as possible. This additional processing doesn’t happen during the initial recording. It’s the job of the mastering engineer to crank up the amplitude so that the tune “punches” when played on FM radio, on your iPhone or through your Bluetooth portable speaker.

It’s not necessarily the best thing for the music but it is standard operating procedure in the commercial music business.

There are lots of creative uses of compression but normalizing is not one of them. Normalizing happens after the compressor/limiter brings down the peaks and flattens the waveform…and the dynamics of the music selection. This is the process that boosts the whole track up to the maximum allowed. If you’re using a PCM system at 16-bits, then normalizing will find the loudest instant in your track and amplify it to the 16-bit maximum AND then raise the rest of the track by the same amount. If there are no amplitude differences in the track (which is likely because of the heavy compression that was applied) then the whole track get maxed out.

That what should have been explained and animated in “The Distortion of Sound”, but it wasn’t. I don’t know why. When tens of thousands of people see this film online or at the Grammy museum, they’re being misinformed.

Suggestions for greater clarity:

Title over amplitude waveform graphics: Audio Dynamic Range Compression and Normalization

Title under center amplitude waveform graphic: Source file heavily compressed

Title under right amplitude waveform graphic: Source file heavily compressed, then normalized to maximum volume.

It should be clear what type of Audio Compression is illustrated.

Probably this is the reason why we keep pumping money into expensive systems with the hope of getting more out of compressed audio files.

If the source was left untouched it would be much easier to setup a reasonably priced system.

I listened to your sample files on my modified PC speaker system – the sound was clear and enjoyable. I imagine the quality of sound on the high end system in the living room. I do not have a system that can playback DASD files yet.

Mark, if that is ‘the standard operating procedure in the commercial music business’, it doesn’t explain the large amounts of clipping found on many pop music CDs. The procedure you describe would yield no clipping.

Actually, it does. In a standard mastering session there a number of steps that contribute to increasing the volume. Compression and normalization are two of them. There are others such as “ultra maximizer” that push even further…and expanders. A common trick is to push past clipping and then pull back .2 dB…that’s why you see so many tracks that aren’t clipped but have a max of .2 dB below full scale.

I felt compelled not to comment on your article but on a recent advertisement which seemed to me to be quite misleading:

Coming August 15, 2014 pre-order your copy today! Orders with both pre-order and in stock items will have all in stock items shipped immediately!

This item not eligible for any further discount offers!

Special Limited Time Sale Price!!!

Limited Run of Only 1,000 First Edition Pressings Available for Optimal Sound Quality!!!

Ultra High Definition 32-Bit Mastering Produced Using PureFlection Process!

This Ultra HD 32-Bit Mastering CD will play on ALL CD players!

First Impressions Music presents Decca: Supreme Stereophonic Legacy, a narrative and musical account of the Golden Age of Decca stereo recordings. Set of 4CDs with beautiflly illustrated book!

Format: 4 First Impressions Music Limited Edition Ultra HD 32-Bit Mastering CDs Plus Book Box Set

$249.99

sale $224.99

Preorder

This advertisement is from the Elusive Disc website and is for the Decca: Supreme Stereophonic Legacy Ultra HD CD Box Set . It seems to me that while 32 bit mastering of the CD is well and good, the standard playback on a routine CD player will be at a 44.1kHz sampling rate and 16 bit word length, correct?

Another interesting article. If you think it’s appropriate, perhaps in Part III or another future article mention using fixed point versus floating point-based software for mixing and mastering and resampling, with the significance that using floating point helps avoid hard clipping with intermediate processing steps. In other words, in fixed point programs a clipping event will permanently harm the signal, while in floating point programs the overage can be carried all the way through processing without any problems for the most part, and only must be dealt with at the final step of creating the digital file for customers.

Great idea…and you’re absolutely right.