No Media Is Perfect: But They’re Not All Equal – Part I

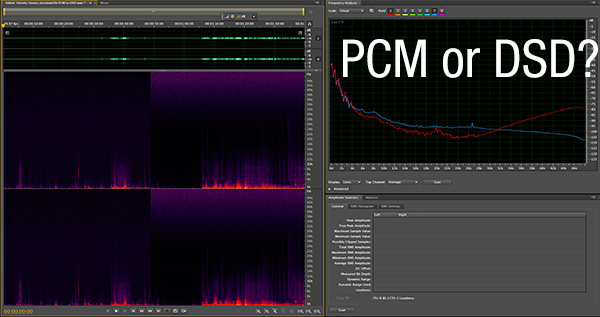

I don’t make it a habit to read the musings of other writers on topics that we cover in common, but a reader pointed out that Steven Stone over at Audiophile Review had mentioned AIX Records the other day. He was writing about the fact that I write about “DSD’s shortcomings” and that he regards my articles as a “giant waste of time and effort”. The article also peeled one of my spectragrms as supporting artwork but doesn’t allow you to enlarge it to see the dramatic differences between DSD and PCM. I have provided the original once again:

Figure 1 – Spectragraph of a PCM and DSD recording of the same piece of music.

The link from the Audiophile Review actually goes to my interview with John Siau from Benchmark Media (he’s a brilliant engineer and it’s his words…not mine…that illustrate the shortcomings of DSD…although I do agree with his position). As you might expect, I disagree with that assessment for a number of reasons. But I did read his article entitled, “DSD and PCM – Horses for Courses”.

It presents a series of arguments on the differences between DSD and PCM. Steven apparently has some background as a recording engineer and advocates for using DSD in certain circumstances and PCM in others. He likes DSD when the ensemble being recorded is playing all together and agrees that PCM is a better format for working in a multitrack environment.

He goes on to say that; “DSD is the best way to archive analog recordings if you need maximum flexibility to release in different digital formats. DSD can be converted easily, without decimation errors into any PCM sample and bit rate. PCM is not so flexible.” Let’s take a look at the realities of archiving and releasing in different formats on physical formats and as digital downloads.

Imagine you’re the owner of a large catalog of very important recordings. All of the masters in the catalog were recorded on analog tapes, which are now stored in a temperature and humidity controlled vault. You determine that it’s important for you protect your analog masters because you know that they will only continue to degrade AND because audiophiles are interested in acquiring them via high-resolution digital download sites. What do you do?

In order to “ensure maximum flexibility”, the best way to archive the tapes would be to transfer them to the best available audio storage formats available. These could include DSD 64 and high-resolution PCM (96/24).

It would not be smart to limit your choice to DSD because the 1-bit technology behind it limits that useable audio band to essentially 20-20 kHz. Although, if you’re planning on making DSD versions available to licensees or you own the DSD technology patents then it makes sense. Transcoding from DSD to PCM makes no sense, just as going the other way is not smart.

Ignoring high-resolution PCM would be a huge mistake. PCM at 96 kHz or even 192 kHz/24-bits provides a much more accurate and much larger potential fidelity workspace than DSD. It doesn’t have a “color” of its own and it doesn’t have a limiting high frequency ceiling. The thought of transferring from DSD to PCM is also a non-starter. Why do a second transfer when you could have archived to high-resolution PCM in the first place?

It’s a little frightening to think that the PCM downloads that some high-resolution digital download companies are selling originated from DSD…and they’re not telling you. There are also companies recording with PCM and then converting to DSD to get the “premium” dollars associated with that format.

To be continued…

Thanks for highlighting Steven’s post. I had a read through the entire article and wondered more about the issue he raised about decimation. This seems to be the criticism (and only one in general) that supports his “lack of flexibility” for PCM. For those projects that require final production into both high-resolution and Redbook standards, does recording in PCM 96/24 format and then down sampling to Redbook standards really affect fidelity?