Pre-Emphasis Part II

Last time, I talked about the use of pre-emphasis (and de-emphasis) in the cutting of disc masters used in the creation of vinyl LPs. The RIAA curves dramatically alters the frequency contour on both the record and reproduction phases — and hope that the electronics are mirror images of each other.

It turns out that the use of pre-emphasis and de-emphasis is standard operating procedure in analog tape recording too. Tape is inherently noisy. The signal to noise ratio of a first generation tape reaches to about 60-72 dB without noise reduction. Electrical engineers figured out a long time ago that adding a pure ultrasonic tone to the program signal improved the frequency response, reduces distortion, and lowers the noise level — but not by a lot. The frequency of the bias is higher than the audio band (typically 50 kHz or higher) making it inaudible during normal playback (it can be heard when scrubbing a tape during editing).

So analog tape recording uses the same pre-emphasis scheme employed by other systems (FM radio, and vinyl LPs). The upper frequencies are boosted during recording and then reduced by the same amount during playback. Analog tape machines need to be calibrated and aligned on a regular basis. In fact, it was my job as a young second engineer to clean, demagnetize, calibrate, and test all of the tape machines in the studio prior to every session — that meant everyday. I got quite good at it.

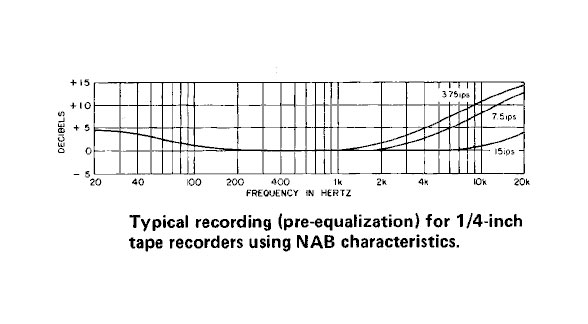

Unlike the single RIAA EQ curve for vinyl LPs, analog tape EQ standards vary depending on the country and the speed of the tape. There are NAB (National Association of Broadcasters) for the United States and another set of standards for European tapes (CCIR/DIN). Makers of tape copies make tapes available in either standard.

The whole concept of purposefully distorting the sound in order to achieve better fidelity has merit. However, there linearity of the frequency response is entirely dependent on matching the pre-emphasis with the de-emphasis curves during recording and playback. In professional equipment with regular maintenance, this isn’t really a problem but inexpensive and poorly maintained consumer equipment can’t be counted on to deliver a flat frequency response.

When it comes to capturing and reproducing frequencies without unwanted deviations from a linear response, analog means are barely up to the task. No matter what designers and manufacturers have tried to do (custom EQ curves like Nagra Master), there are always challenges. And don’t forget this is without Dolby noise reduction, which introduces an additional pair of encode and decode conversions.

Two points:

1) The Wikipedia article “RIAA equaliztion” points out that before 1954 there was no standardization, with over 100 curves in use, though standardization was mostly in place by the time of the stereo LP, but noting that “It is possible that some niche record cutters were still using EQ curves other than the RIAA well into the 1970s. As a result, some audio manufacturers today produce Phono Equalizers with selectable EQ curves, including options for Columbia, Decca, CCIR, and TELDEC’s Direct Metal Mastering.”

2) The theoretical Achilles’ Heel of Dolby noise reduction has always been that the encoding and decoding processes *cannot* be symmetrical. In recording, it is unambiguous to boost signals that are below a certain level, but the result is that there is a volume range after encoding that contains *both* quieter signals boosted into that range and signals that were in that range in the first place and had not been boosted.

Therefore, in playback there’s no way of knowing which of the signals in the bottom volume range are those that had been boosted in recording and which are those that had not been boosted and are still at their original level just above the threshhold for boosting.

To attenuate all signals below a certain level on playback will definitely expand dynamic range, but at the cost of attenuating some signals that hadn’t been boosted in recording.

This applies just as much to professional multiband “Dolby A” as it does to single band consumer “Dolby B.”

In fact, since tape hiss is mainly a high frequency problem, doing this kind of volume compression and expansion at lower frequencies introduces a problem larger than what existed before. The consumer version, focused only on the higher frequencies, would seem to be the cleaner solution.

And I thought part two would be about the redbook pre-emphasis.

I think we need pre-emphasis and de-emphasis for hirez material. Like the 384 khz sampled stuff. The signal levels are so low we probably need to use a reverse brown noise curve. So probably start at 20 khz and go to plus 20 db at 192 khz frequency.

Won’t work for DSD alas as it already has too much noise up there to make boosting it practical especially with only one bit to work with.

Dennis, you’re right that emphasis was routinely used for early Redbook CD mastering. But that was a long time ago. It hasn’t been used in many, many years.

Linear distortions are correctable…up to a point. Even non linear distortions are correctable if they are carefully thought out and calibrated like Dolby A. Digital software tools have brought old recordings with defects remarkably back to life but they require tedious and expert handling to work.

What about AFTER those distortions are corrected. High end audio manufacturers have taken away the means to correct any and all remaining linear distortions. No more tone controls. No more loudness contour controls for low level listening. No more rumble or scratch filters. And they don’t want you to use an equalizer. Far more profitable to keep you shopping and swapping for expensive wires instead which of course don’t work for more than a few of your recordings which is why you keep swapping.

Once upon a time, when large studios with a lot of money made most recordings, studio technicians used calibrated microphones, frequency sweep generators, and real analog spectrum analyzers to calibrate monitor speakers usually about once a week. Many studios even used similar monitor speakers, Altec in the US, Tannoy in England. Their designs and performance weren’t all that different. But today, every studio has its own idea of what a monitor speaker should be and coming largely from the realm of audiophiles they too do not want their monitoring systems calibrated to any standard.

What are the results? There are definite spectral balance variations among different brands of legacy phonograph records. There are definite differences in the spectral balance of phonograph cartridges, many with a nasty treble peak due to undamped resonances. Some are cheap for use in low end systems like Pickering. Others are expensive like Ortofon. The worst I ever heard came from ATC but there may be even worse out there. It’s often about +5 db at 15 kHz and makes them sound “zippy” to tyros. But CDs are in a league by themselves. Their spectral balance is all over the map. Every one is different and needs its own correction, even from the same brand. I’ve got two Dixieland jazz CD recordings from Green Hill Records. They have successive catalog numbers. Same musicians, same instruments, same arrangers, same studio, same equipment, two different recording engineers. Equalize one to get accurate tonal balance and the other is off by a country mile. Doesn’t matter which one you pick to adjust to, the other will be way off if it isn’t readjusted. Can you do this with modern high end audio equipment? NO! They have taken that away from you. This is only one of many reasons I reject their industry. I put this flaw in the category of failed systems engineering. High end audio manufacturing industry, as one engineer to others, I give you a grade of F minus for your products even if they were reasonably priced. If the rest of your customers knew what I know, your industry wouldn’t exist.

Good comment Soundmind. There is one point I not fully agree. There are High End manufacturers like Classé audio, having DSP based preamplifiers with bass and treble functions, as well as parametric EQ. Even a tilt function is available. This is grace to modern digital technologies and shifting of D/A conversion into pre- and integrated amplifiers. There are not many of this kind available so far and a part of the market will still stack to legacy technologies and thinking.

Cheers

Fritz

Mark, this was a great write-up. Thanks!