How to Read a Spectragram: Part III

Over the past couple of posts, we’ve looked at the spectra of a standard definition compact disc and a great example of a high-resolution file with lots of ultrasonic information. The previous examples were digital recordings…meaning the original source recording was done using PCM digital recording equipment. What can a spectragram tell us about a recording that was originally recorded on analog tape?

There are a lot of classic recordings that were originally recorded on analog multitrack machines, mixed through analog mixing consoles and recorded on stereo 2-track mixdown analog recorders. Even today, there are producers and engineers that prefer the sound of analog tape over standard and high-resolution digital. It’s true that there is a particular sound associated with analog tape. There are digital “plug-ins” that can emulate the distortions and “sound” of analog tape but there’s nothing quite like the real thing.

But what does recording on analog tape look like on a spectragram? First, we have to transfer the analog master through an analog to digital converter to create a spectragram. But what sample rate should we use? Can we get away with 44.1 or 48 kHz? Or do we need to move up to 96 kHz? With the right equipment, we could conceivably do the conversion at 192 or 384 kHz! Of course, there are tradeoffs that must be considered if we opt for one of the very highest sample rates. Every time we double the sample rate, the size of the recorded digital file doubles. All this extra data just to be able to get another “potential” octave to the transfer.

Well, what if the analog tape doesn’t contain any high frequency information that would require the use of very high sample rate. If a first generation analog tape can produce around 30 kHz then 96 kHz would more than capture it, right? We know this because half of 96 kHz is 48 kHz, the highest frequency recordable with a 96 kHz system according to Nyquist. It would seem that using 192 or 384 would be completely useless…and it is! Despite what some manufacturers tell you in their flashy brochures and websites, transferring an analog tape master at rates higher than 96 kHz is not going to translate into a better sounding digital file.

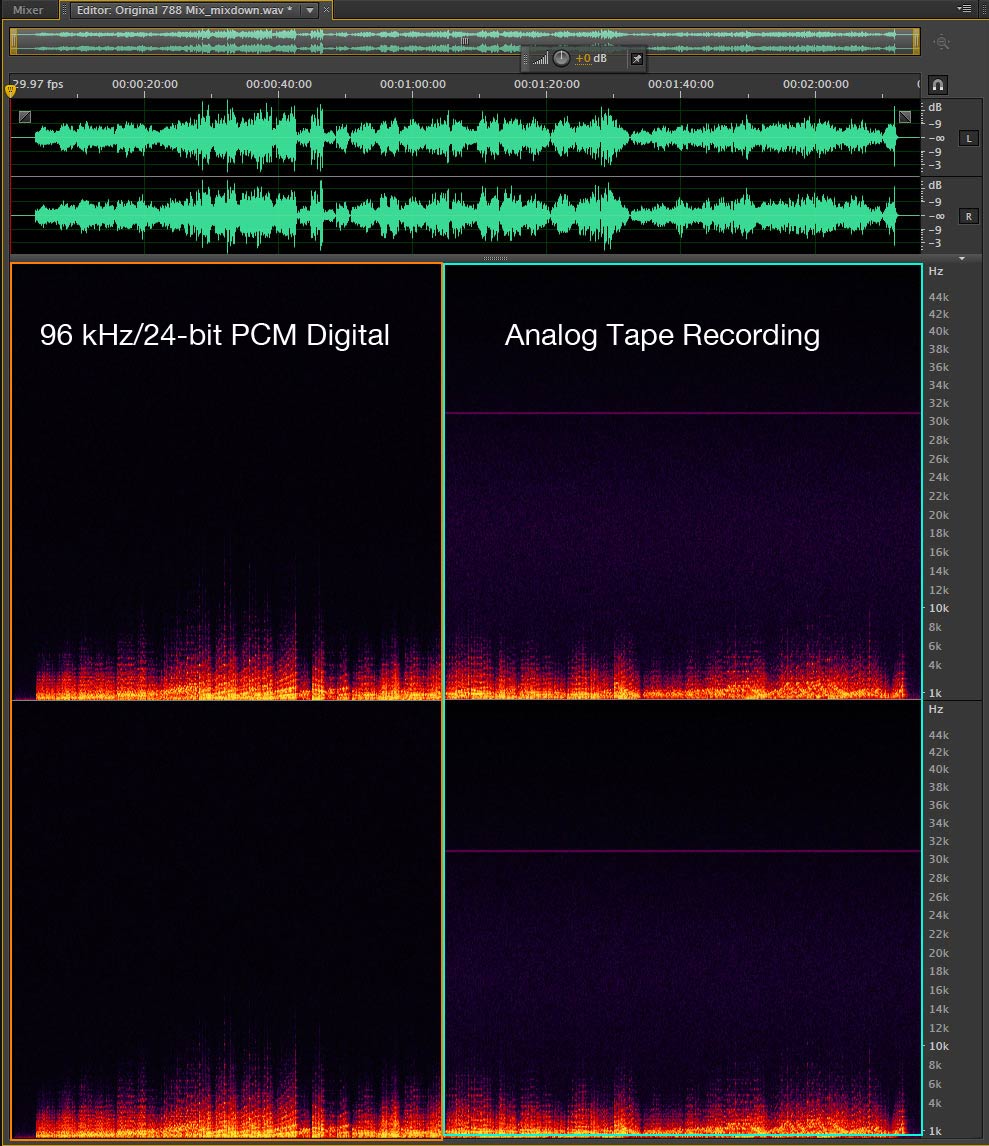

Figure 1 below is a spectragram that shows both an HD-Audio plot AND the same piece of music recorded on analog tape. The sample rate is 96 kHz in both halves. Notice the clean black higher frequencies of the digital recording. You might also notice that there is not a lot of ultrasonic information present. The track is of a solo piano, which doesn’t contain a great deal of high frequency information…at least as compared to an acoustic guitar, percussion setup (with lots of metal instruments) AND acoustic bass.

Figure 1 – The spectragram of an HD-Audio PCM track next to one from an analog tape. [click to enlarge]

The analog tape plot is very interesting. The first thing to notice is the faint purple horizontal line at about 31.5 kHz. That is the bias frequency of my NAGRA IV-S analog tape machine. All modern analog tape machines use a bias current added to the record signal to improve the performance of analog tape recording. It’s clearly a component of the recording but is deliberately outside of the usual “audio band”. In fact, you can actually hear it when you scrub an analog tape while editing. It shows up as a squeak sound.

The other thing to notice is the overall purple color above about 12 kHz…this is “tape hiss”. It is random high frequency noise that unfortunately is part of the analog tape recording process. There have been various systems invented to try and combat hiss on both the professional and consumer end. Remember Dolby B on your cassette deck. We also had Dolby A in the studio and later Dolby SR.

So it’s not difficult to identify an analog recording using a spectragram. There will be more high frequency noise, a visible horizontal line that is the bias and a clear high frequency ceiling. There really is not place to hide.

So what does this mean for digital download services that claim they are making high-resolution downloads available of older analog recording. They are delivering standard definition analog copies in digital bit buckets that are mostly empty.

Tomorrow, we’ll look at files that are clearly misleading.