Pre-Emphasis: Part I

It was very busy Thanksgiving weekend at the Waldrep household. I’m ready to get back to the university and my normal schedule tomorrow. It’s always crazy with the traditional holiday feast but our family has the added attractions of our wedding anniversary, two birthdays in the immediate family (my wife and youngest son were born on the same day), and two of my wife’s siblings also celebrate birthdays over the weekend and they live just an hour’s drive up the coast. This year also brought a reunion of sorts with my Colorado-based sister and her family (brother-in-law, two daughters and a boyfriend). They visited on Friday. We took a trip down to the beach and shared the sunset from the local bluffs with the rest of the neighborhood.

However, today I got back to my book project and worked on the chapter about music formats — including vinyl LPs. I’ve been writing a lot and am nearing the end of the project. The illustrations are almost finished and I have only a couple more chapters to complete. Thanks for your patience and support over this past year. I’m about 9 months late but I’m confident everyone that has ordered the book and disc (or eBook and files) will find it compelling, informative, and worth the wait.

This post is about pre-emphasis. You may not know that it’s necessary to alter the normal frequency response of a source master in order to optimize the final output fidelity. And it can be applied to both analog and digital formats. Pre and post emphasis is why there is a separate PHONO input on your AV Receiver of your dedicated preamp. The modifications applied during disc cutting are “undone” when played back at the consumer end.

Recording audio into the grooves of a spinning piece of lacquer or vinyl is an imperfect process for a number of reasons. One of the biggest problems is the requirement for disc equalization — the deliberate altering of the frequency response of the recorded and reproduced signals. It’s required because cutting heads and pickup cartridges are traditionally velocity transducers. That means that the speed of the physical movements of a cutting head or phono cartridge stylus is converted from or into an electrical signal — not changes in amplitude.

In order to understand how modulating the walls of a record groove demands equalization; you have to understand that an ideal disc recording would have consistent lateral movements of the cutting head and playback stylus. We don’t want bass frequencies taking up more room than higher frequencies or the goal of a “long playing” recording would be lost. In order to maintain uniform groove widths, we want constant amplitudes at both ends of the audio spectrum. For example, a 100 Hz tone or partial shouldn’t take up any more space than an identical tone at 10 kHz.

To master a lacquer disc with constant amplitude, the audio signal sent to the cutting head can’t have a flat frequency response. A disc cutting head is an electromagnetic apparatus and therefore cuts a groove proportional to the voltage of the audio signal as a velocity.

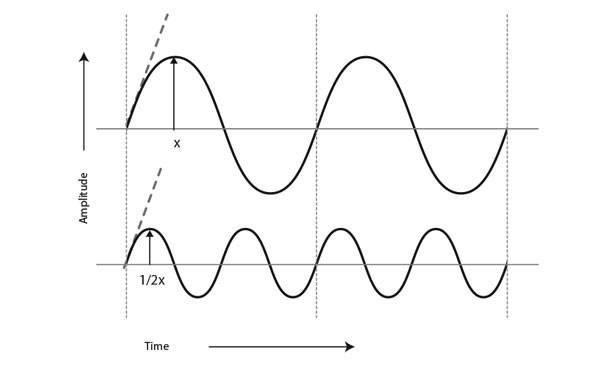

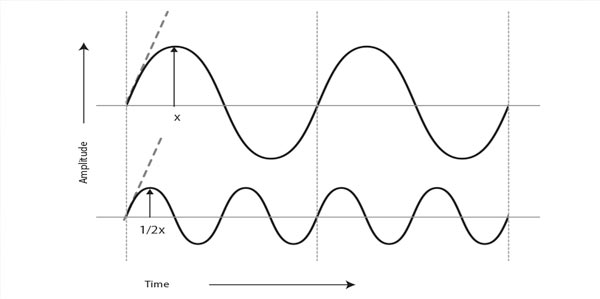

The figure below contains two sine waves. The upper waveform is in phase with the lower one but has a frequency twice as fast. The point where the signal crosses the zero amplitude line represents the peak velocity of any sine wave and is defined by the frequency and amplitude of the signal. Higher frequencies are attenuated by half to maintain the same velocity. Take a look at the figure and notice that the amplitude of the faster — lower sine wave — is half the amplitude of the slower one. Therefore, a disc cutting head receiving an audio signal with flat frequency contour will cut high frequencies with lower amplitudes than lower — bass frequencies.

Figure 1 – Two sine waves with the same peak velocity – notice the frequency of the lower wave is twice the rate of the upper wave.

This would be problematic because we want the original frequency response as established during the mixing and mastering sessions to be reflected in the final distribution media. The solution is to emphasize the high frequencies during disc cutting and attenuate the bass. This results in a groove that maintains a relatively consistent width. This is known as pre-emphasis and is a common technique in audio signal preprocessing.

To be continued…

To master a lacquer disc with constant amplitude, the audio signal sent to the cutting head can’t have a flat frequency response. A disc cutting head is an electromagnetic apparatus and therefore cuts a groove proportional to the voltage of the audio signal as a velocity.

Wow. At 63 I’m still learning. Never once gave any thought to this. Thought it was flat all the way. Thanks for the revelation.

There’s a lot of stuff like this in the book. Stay tuned.

Not only would bass take up too much space on a record without a substantial cut, no phonograph cartridge could track it. As for the treble it would be overwhelmed by noise. The RIAA curve standardized pre-stamping equalization and spans a range of about 40 db. Inaccuracies in the inverse equalization curve due to incorrect design or an electrical mismatch between the cartridge, wiring, and preamp equalization including the input load will result in a systematic FR error on top of all others inherent in the system. Same goes for analog tape. There the standard is NAB. Same for FM broadcasts where the standard is 75 microseconds. Without these huge equalizations (40 db is a factor of 10,000 to 1) these technologies wouldn’t work.

A typical phonograph record undergoes at least 6 equalizations not counting the hands of the balance engineer. 2 NAB on the master tape, 2 on the mixdown tape, and 2 in the RIAA recording and playback of the vinyl. Six, count ’em up audiophiles.

Then along came Dolby A professional. This from the point of view of audiophiles who hate the thought of equalization is the audio equivalent of making sausages. You don’t want to think about it. Chop up the input signal into 4 bands, equalize each band separately where unlike NAB and RIAA the degree of equalization depends on instantaneous loudness due to dynamic compression, tape it, recover it, expand and de-equalize it, and if all is perfectly calibrated then you get your signal back with less tape hiss. Of course this is really only necessary for adult music as children’s music has little dynamic range and what there is of it is compressed further to make it as loud as possible on a radio. 14 equalizations minimum audiophiles and dynamic compression and expansion where the signal is disassembled and reassembled. Sausages anyone?

How is quantization error treated in your recordings ?

I record with 96 kHz/24-bit PCM technology and state-of-the-art converters. At 24-bits and with dither, quantization error is minimized to a level where it doesn’t impact the fidelity.