Upgrading Lossy Music Files

Audio researchers at Yamaha, Denon, Harman Kardon, Sony and few other companies have developed and deployed technologies that promise to sonically restore the stuff that is removed by “lossy” compression algorithms. I visited this topic a few months ago when I analyzed the DSEE [Digital Sound Enhancement Engine] process that Sony developed and includes on their new high-resolution playback machines (click here to read that post).

The basic concept is that the fidelity of a music selection prior to being encoded as a lossy MP3/AAC can be “restored” by a few fancy signal-processing algorithms. It certainly true that once a file is digitized that all sorts of creative things can be done to change the sound. The power of DSP (digital signal processors) and the clever algorithms that run on them have brought revolutionary possibilities to audio.

I attended the NAMM (National Association of Music Merchants) and happened by a small company that had developed a “repitching”software tool. As the guy played a chord on his small MIDI keyboard the tonality of a Michael Jackson tune was instantly changed. Imagine a completely mixed stereo track switching from major to minor mode at the touch of a few keys. I was very impressed!

So it would not seem out of the realm of possibility that the DSP gurus at Sony or Harman could coax some fidelity back into a lossy compressed music file that had been stripped of some of its high-frequency content. Unfortunately, the marketing claims exceed the realities. I thought I would reopen this subject with the Harman Clari-Fi processing that is built in to the HTC One M8 HKE Smartphone, which features prominently in their advertising.

There’s a lot of complexity here. What compression algorithm was used to convert the original file to the lossy format? What bandwidth was used? How much fidelity was in the original file prior to the conversion?

I took the Laurence Juber “Mosaic” track (a track that has universally been recognized as a great example of real HD-Audio and which won the 2002 CEA “Demmy” award) and converted it to a series of MP3 files. I set the parameters of the conversion to CBR (Constant Bit Rate) 64, 96, 128, 256 and 320 kbps. These levels range from really poor to very good. HD Radio, for example, uses 64 and 96 kbps (makes you wonder why they used the HD initials…or not), the majority of music downloads are done at 128 (iTunes Plus uses 256) and if you purchase an MP3 from iTrax (yes, it happens), the files are encoded at 320 kbps.

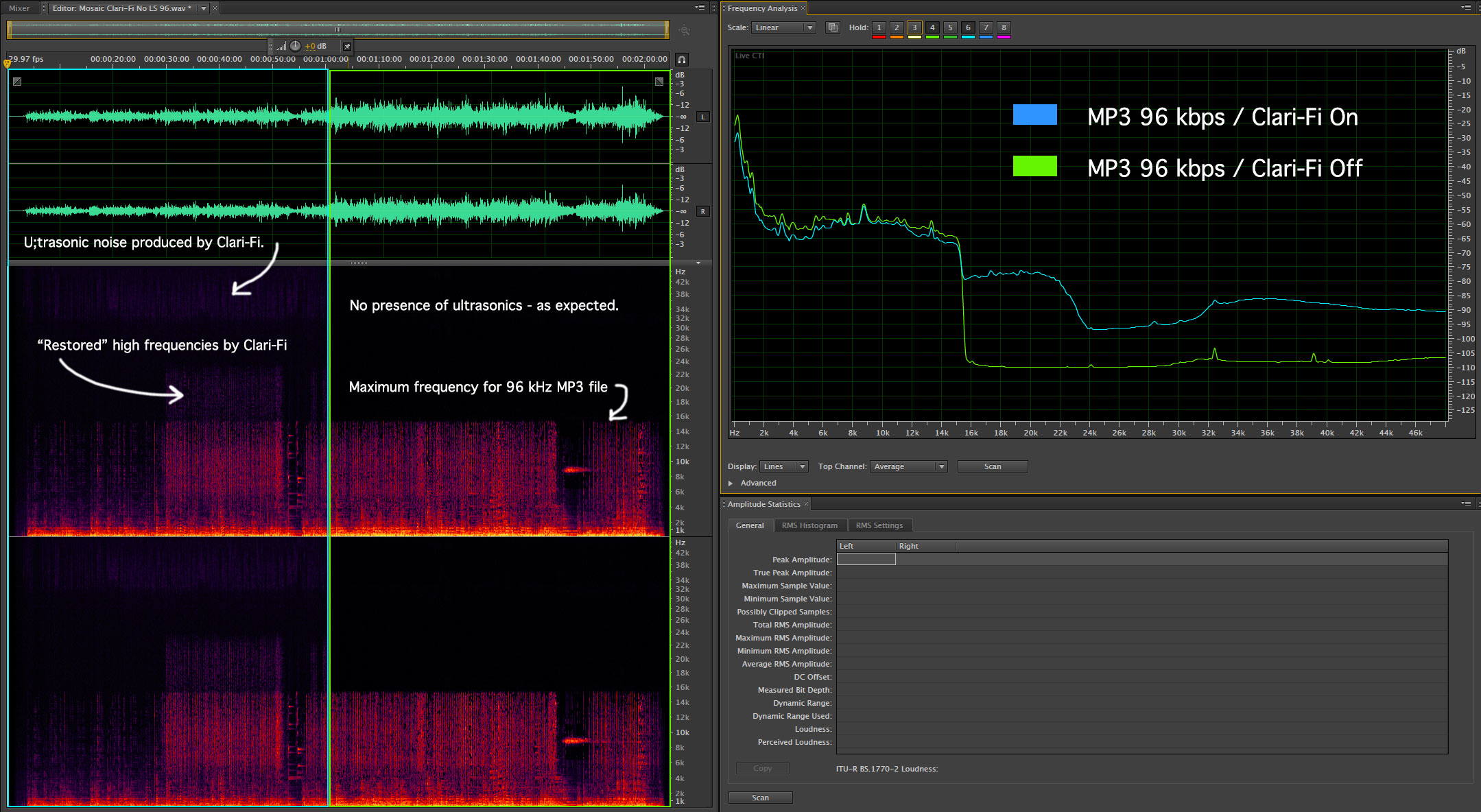

I loaded these files onto the HTC phone and captured the stereo analog output back to PCM digital files at 96 kHz/24-bits. I did this with the Clari-Fi algorithm turned off and then with it turned on. Finally, I did the usual spectral analysis on the files. Take a look at the first example below:

Figure 1 – The illustration shows a 96 kbps MP3 file of my HD “Mosaic” track with and without the Clari-Fi processing. Note the additional high frequencies AND the ultrasonic noise that was added. [Click to enlarge]

My initial thought is why bother with the whole Clari-Fi thing? People that choose to listen to MP3 files encoded at 96 kbps deserve what they get…terrible sound. And it’s not just the lack of frequencies above 16 kHz. There’s a lot more stuff that is thrown away at this level. The sonic impact of a the extra high frequencies is minimal at best.

I’ll write tomorrow on the use of Clari-Fi on files that have higher bandwidths…like 256 and 320.

HD actually stands for Hybrid Digital – though that phrase was abandoned and the company that owns the HD Radio technology now says it doesn’t stand for anything at all.

Hybrid Digital refers to the superimpostion of a digital subcarrier on an FM signal.

FM Stereo was required by the FCC to be backwards compatible with existing (mono) FM receivers. That was accomplished by having the main carrier send the mono L+R signal, and putting a second subcarrier at 19Khz with the difference between the channels: L-R. That meant brickwalling the main carrier at 15Khz to leave room for the “stereo subcarrier.” The receiver would make two copies of each signal and add one pair together in phase and one pair together out of phase. The audio algebra looked like this:

(L+R)+(L-R)=2L

(L+R)+(R-L)=2R

Emboldened by the fact that this worked, Muzak was distributed on another subcarrier, further degrading the sound.

HD Radio places up to three digital streaming subcarriers on an FM Stereo station.

HD1 duplicates the main carrier’s program, and just as a stereo radio will automatically switch into stereo, an HD radio will automatically switch over to HD1

HD2 can be entirely different programming from the main program.

HD1 and HD2 are of reasonable streaming quality, and when stations distribute them on the web they use 128Kbps mp3 for that.

HD3 is the poor relation, designed for weather reports, with half the bandwidth of the others.

And that’s what HD is.

Thanks Phil…the folks at iBiquity piled on the “HD” bandwagon. They’ve fooled a lot of people into believing that their additional channels are high-definition, when in fact they’re less than the worst MP3 you’ve ever heard. I wrote about HD-Radio a while back.

HD1 and HD2 streaming digital has one advantage over FM-Stereo: it doesn’t have to be brickwalled at 15Kh – at least the version of those stations carried on the web at 128kbps mp3. HD3 channels, on the other hand, are typically distributed over the web as 64Kbps streams, which top out at 11Khz.

While the internet radio station I listen to most often, WBGO-FM “Jazz88” New York / NJ, streams at 128k, the effort to revive pioneering “free-form” rock station WBCN in Boston, which is being spearheaded by its first (1968) program director, Sam Kopper, which is no longer on any main carrier, has been relegated by CBS, which owns it, to an HD3. Its streaming was therefore at 64k for several years, but.Sam finally got that raised to 128k.

If you want to listen to the rebirthing of that iconic station, which was ground zero for the antiwar movement, point your browser at WBCNBoston.com to have it come up in the CBS radio player. Though it’s automated nights and weekends, he’s live from a bus he’s outfitted as a mobile recording studio/DJ console weekdays 10-5 (Fridays he goes into the early evening). He’s training new DJs and uses a facebook page “WBCN The Rock of Boston” as a live chat board during the day, where listeners can make requests and kid around with the DJs and each other.

The format is wide open, with music going back to early country and r&b and some jazz, through current releases – though the main emphasis is on sixties rock and its descendants.

Mark, in your article I quote; “And it’s not just the lack of frequencies above 16 kHz. There’s a lot more stuff that is thrown away at this level. The sonic impact of a the extra high frequencies is minimal at best.”

As someone who cannot hear frequencies above 12.5KHz, I wonder what is the other stuff that is thrown away – is it below the 16KHz level? If it were only information above 16KHz, then you are saying it would not be that bad?

Really enjoy your insights, thank you.

Lossy compression schemes not only remove high frequencies but they also throw away other partials in the lower frequencies that are “masked” by nearby tones. You can’t get these back.

Mark, I still find it mind boggling that the whole reason for mp3 files seems to have become lost in the mists of time. Only a few years ago dial-up was all the rage, 56kbps was “fast” but too “slow” to move uncompressed audio formats such as wav files from machine to machine. Enter the mp3. Horrible sound, but at least it could be moved via dial up and played on dreadful little computer speakers. Storage space cost a small fortune and was at a premium.

Today, dial-up has almost gone the way of the Dodo – even in the USA. Cable and Fiber internet connections are normal. Terabyte drives cost $50. Portable players sport Gigabytes of storage. Internet Video is disrupting the broadcasters. The whole reason/need for mp3s has disappeared. Just as Black and White TV gave way to color, and NTSC gave way to ATSC. The mp3 standard needs to be consigned to the scrap heap of technology.

Yet as you noted only a few days ago, 10% of people think that music truly recorded in high definition should sound like mp3s with all the nasty noises from compression. But then even the introduction of ATSC wasn’t without people saying that they couldn’t see the difference between 480i and 1080p.

For me, putting 1 gallon of gasoline in a 5 gallon bucket doesn’t make the gasoline “HD”, it’s just in a bigger bucket and takes up more space. If it’s redigitization of an analog source from 30 years ago, all it does is wastes some bandwidth and disk space. It most likely won’t sound any better than the original CD cut when the tape was new.

But getting full dynamic range that 24 bits can give and the extra octave from 96KHz sampling makes the music – well, music without all the artifacts of the old way compressing the life out of the source.

Keep up the good fight for real HD and keep the articles coming, you’ve always something interesting to say.

Mark,

In your post you mentioned “re-pitching” and then went on to say that one could switch from major to minor mode with the touch of a few buttons. I am no audio expert, but, I do play the piano. While I can imagine changing the frequency of a phrase of music to raise or lower the pitch in that phrase (or track or some other grouping of notes), a changes in modes requires changes in individual notes, not the entire phrase. That would be one smart algorithm. Can it really change modes?

It really did! I was very impressed. The person doing the demo was able to play a D major chord (the key of the piece) and then fatten the 3rd and the whole track was now in the minor mode.